For some time now, there have been concerns that microplastic particles eaten by fish could be passed along to human seafood consumers. According to a new study, though, such may not be the case with sea bass, and possibly not with many other fish.

Currently found in both freshwater and marine waterways around the world, microplastic pollution takes the form of tiny plastic particles that enter the environment from sources such as disintegrating trash, aging tires, synthetic fabrics, and personal care products including shampoo and cosmetics.

Unfortunately fish do eat these particles, which pass through their digestive system and often even enter their bloodstream. It has therefore been surmised that when people eat the flesh of those fish, they may also be consuming microplastics that are present in the tissue.

In order to gauge the likelihood of this happening, a study was recently conducted at Germany's Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research. Led by Dr. Matthew Slater, the scientists started with a lab-based group of adolescent European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), and fed them fish-feed pellets laced with a microplastic powder for a period of 16 weeks.

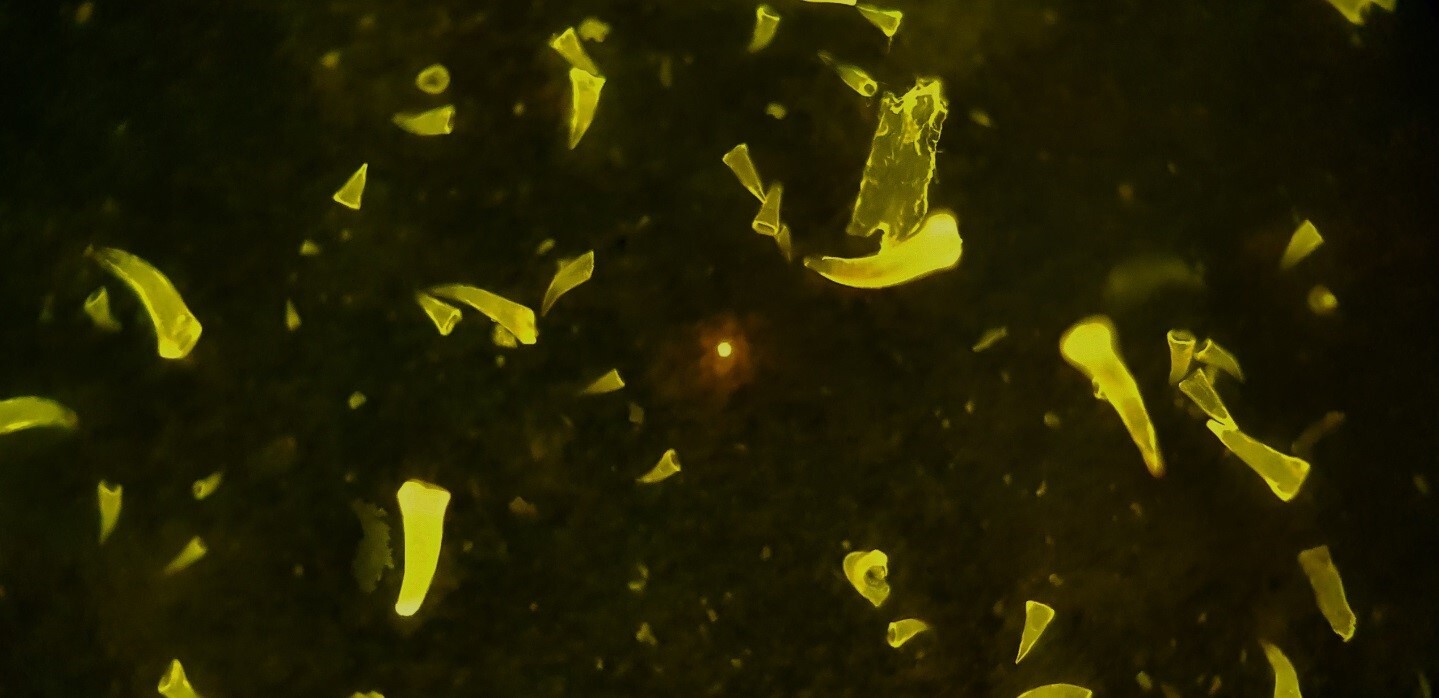

While the pellets themselves contained fish meal, wheat bran, vitamins and fish oil, the powder consisted of yellow-orange fluorescing plastic particles measuring one to five micrometres in width – this represents the smallest size category of microplastic pollution. It is estimated that each fish ingested about 163 million of the particles over the 16-week period.

The researchers subsequently gutted and filleted the animals, then heated the fillets in caustic potash, causing the muscle tissue to dissolve into a fluid. That liquid was then passed through a filter which captured any plastic particles that might be present. A fluorescence microscope was used to count those particles.

It turned out that for every five grams of fillet, only one to two particles were present. Even those may have been located in residual blood that was left in the fillet, as opposed to in the actual muscle tissue itself. What's more, even though the fish were exposed to microplastics concentrations far higher than what they would encounter in the ocean, they grew well and were reportedly in perfect health.

"I believe the sea bass results provide some indication of the response of other marine finfish to microplastic ingestion, however this remains untested," Dr. Slater tells us. "Equally, we studied only one type, size and specific shape of microplastic within the study. Microplastics in the marine environment are unbelievably diverse. Our results provide some indication of uptake in the broader marine environment however there are many (many!) other types left to be tested."

It is additionally possible that in the open ocean, plastic particles may absorb pollutants that are passed into the flesh of fish, even if the particles themselves aren't.

A paper on the study, which also involved scientists from the University of Bremen and the IBEN laboratory, was recently published in the journal Marine Pollution Bulletin.

Source: Alfred Wegener Institute