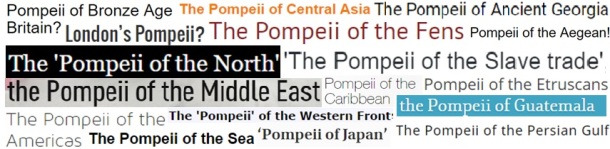

For years Pompeii has been many things. The subject of art and novels, the setting of films, a Lego model and a cake. So potent is the imagery the Roman city inspires in people’s minds that it has let many other places borrow the name. It seems like you cannot open a news or travel site these days without bumping into a ‘Pompeii of’ somewhere. There’s a ‘Pompeii of the East’, an ‘icy Pompeii’, a ‘Pompeii of the Midwest’, a ‘Pompeii of the Pacific’ and many others. Prof. Peter Kruschwitz of the University of Reading has even created a helpful list of many of the different Pompeiis on his blog The Petrified Muse. I don’t know if all these examples are the result of an archaeologist trying to excite a scribbling reporter or the result of a reporter trying to enthuse a scrolling reader, but it certainly works. Being a Pompeii brings curiosity and fame, since the ancient city is, in the words of David Shariatmadari, a ‘blockbuster ruin’. All of these places claim the connection either through a history of disaster or, more commonly, through the state of their preservation. These links, however, can often be quite tenuous.

This naming trend is not a recent phenomenon. There are lots of examples from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries where Pompeii was cited. The New York Times seems to have been fond of the practice: there was a mention of an Irish Pompeii (18/8/1872), a Japanese Pompeii (19/9/1874), a ‘Pompeii of the Middle Ages’ (17/3/1901) and a ‘Pompeii of Britain’ (6/7/1913) just to name a few. In my searching I also found a bizarre article in the newspaper about the amount of deaths caused by speeding cars. The article began by comparing it to how many ordinary people trying to flee the eruption would have been killed in Pompeii by the speeding chariots of the wealthy (14/4/1912). It’s an odd comparison which shows that apparently invoking Pompeii can be useful in all sorts of situations!

Pompeii: the original version

Like most of the more recent articles I mentioned at the start, the early examples of cities compared to Pompeii also rarely featured a volcanic eruption. Another story from The New York Times speaks of the city of Sipuntum in Italy which was found around the time of writing (4/2/1878). The ancient site slowly started sinking into the ground while it was still inhabited probably due to earthquake activity. According to the article, Emperor Frederick II finally moved its population to another town in 1251. The article’s author writes:

‘thenceforward old Sipuntum was deserted and handed over to the earthquakes, which seem to have dealt with it tenderly, not rudely shaking it into ruin, but wrapping it in clay and tufa sand so effectively as to hide it away for six centuries’.

I only wish today I could find a newspaper article (or even an archaeologist…) that spoke as affectionately about clay.

Ostia, also somewhat confusingly called the ‘Pompeii of Rome’

Another article, this time from The Times of India, calls the Roman city of Calleva near Silchester a ‘British Pompeii’ (21/6/1898). The article begins with a wonderful quote about some friendly competition:

‘the world famous Museum at Naples will have to look to its laurels. The rich yields of buried Pompeii have filled it with antiquity and rare treasures to an extent that gives it an [sic] unique advantage over other collections. But in one respect the Reading Museum has beaten it.’

The author then goes on to describe three wooden tubs that were found at Calleva. These were originally used as wine containers which, once dry of their contents, were repurposed as the insides of a well. The author posits that nothing like this could ever be found in Pompeii because the volcano destroyed wooden items. This is not strictly true since we have found carbonised wood there, but here we can see that, while it is great to have found another Pompeii, it is even better to find something that beats it. Despite these discoveries, over a century later Calleva has not reached the same level of fame as the original Pompeii, but I’ve been told the museum is certainly worth a visit. Coincidentally, when speaking about the newest ‘British Pompeii’ which was found in 2016 in Cambridgeshire, the site director Mark Knight even said that with this find ‘we’ve out Pompeii’d Pompeii’. So the competition continues.

Priene called the ‘Pompeii of Asia Minor’ on a panel in the Altes Museum in Berlin

Stories of Pompeiis can be found all over the internet in all sorts of contexts. Sometimes the metaphor is about a place, but in a different way to the examples above. For instance, Chernobyl has been called both the ‘Pompeii of Communism’ and the ‘Pompeii of the Atomic Age’. Sometimes the comparisons have nothing to do with people anymore and we get the ‘Pompeii of Animals’ and the ‘Pompeii of Trees’. In other cases it is just a metaphor for disasters unattached to any location like the ‘Pompeii of bitcoin’ referring to a case of theft or, actually completely unsurprisingly, the ‘Pompeii of politics’ that was the US election late last year (thanks to The Petrified Muse blog for finding that one!). Perhaps my favourite of all the uses of the city that I found while Googling comes from a post on the Farmscape Gardens blog which features this quote:

‘Sometimes the real glory of the mashed potatoes is not in the fluffy white. It’s not in the gravy filling the soft crater and Vesuviusing down onto the Pompeii of peas beside.’

Pompeii can truly be anything.

Over the years the city has become much more than the sum of its material remains. We feel sorry for its victims, admire its frescoes and idolise its wheel-rut-covered streets (I’m looking at you, the twitter #rutporn crowd…). When we make the comparisons to new discoveries I hope we also remember the differences between them and not blend ancient (and modern) sites into one big mass of broken stuff. Even as its columns and buildings crumble, Pompeii is here to stay in our imaginations, so we should take the time to learn about all the other places, and remember their real names. Comparisons can be good because they can make us ask new questions or see something in a different light, but we should not let them take over. We won’t be forgetting about the Roman city any time soon, but we don’t want the whole world of archaeological remains or human disasters to be so easily flattened into a nothing but a series of Pompeiis.