This post is part of Outward, Slate’s home for coverage of LGBTQ life, thought, and culture. Read more here.

Those currently enthralled with Netflix’s hit competitive glass blowing show Blown Away may be justifiably curious about the presence on the program of “glory holes.”

For most of the culture, this terms refers very specifically to a public, quasi-anonymous sex act involving gay men, bathroom stalls, and a handily placed hole. For glass blowers, the glory hole is a high-powered furnace burning at over 1000 degrees Fahrenheit—hardly suitable for sex acts of any kind. So why do they call it that? Which glory hole came first? Which group owns the term “glory hole”? Would a glory hole by any other name smell as sweet? How did we get to me asking these questions?

Let’s start at the beginning.

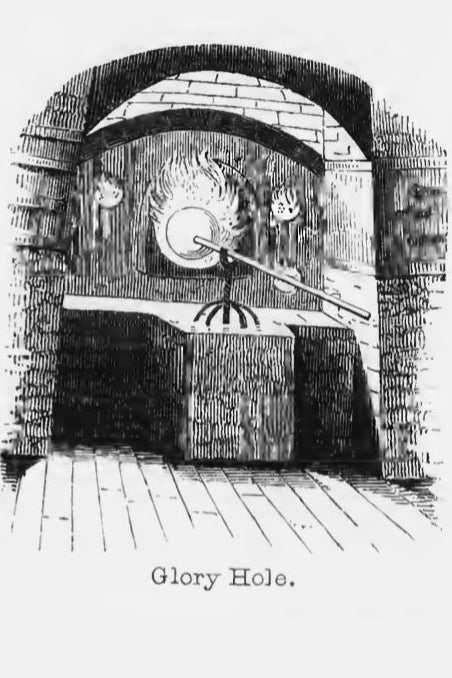

Obviously, glass blowing, much like sex, is an age-old practice. The first use of glass has been tracked to Egyptian techniques dating back as far as 1500 B.C. The earliest evidence of blown glass dates to the Ptolemaic period, around 350 B.C., where the technique was developed for flask-making. It was from the Ptolemies that the tube-blown glassmaking techniques we see today derive. The earliest evidence found of the kind of glass furnace with what would come to be known as the “glory hole”—a furnace specially used to partially or completely reheat unfinished glass for the purpose of shaping or polishing it—comes from a 1023 A.D. manuscript by a Benedictine monk named Rabanus Maurus, depicting a glass furnace as a multilevel cylindrical structure.

According to glass historian Robert Charleston, among the essential features of this illustration is the structure’s middle chamber, where “multiple ‘glory holes’ give access to the glass pots.” By the time of the Renaissance, glass blowing techniques were perfected as an art form and a science. For early modern glass blowers, glory holes were already part and parcel with the craft; they just weren’t called “glory holes” yet. That name wouldn’t arrive until well into the Industrial Revolution.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first recorded use of “glory hole” in English comes in 1825, when it was described as “a receptacle (as a drawer, room, etc,) in which things are heaped together without any attempt at order or tidiness.” Twenty years later the term made its slang debut, being used to describe “a filthy, stifling cell” or small room for “degraded beings,” such as prisoners. (Surely, this is a prescient definition, considering the cramped bathroom stalls the term would popularly come to describe over a century later.) The first recorded use of “glory hole” in glass blowing appears in an 1849 text called Curiosities of Glass Making by English glassware manufacturer and politician Apsley Pellatt.

The best arrangements for annealing may be foiled, should the Glass-blower unnecessarily lose time after finishing the work; as the hotter the goods enter the arch, the better; on this account, the large goods receive a final reheating at the mouth of a pot heated by beech-wood, and called the Glory Hole.

As the glass manufacturing industry grew, so did the term’s usage. One reason for its adoption, according to the Museum of Glass in Corning, New York, may have been the visual phenomenon that the furnaces produced in glassmaking factories themselves; the surreal effect of light beaming from the 2100-degree furnaces, piercing the smoke-filled factory air and creating an “illusion not unlike that seen in paintings of saints and angles where ‘The Glory’ radiated from their heads.”

So what about the gay meaning? In 1707, more than 100 years before glory hole entered the lexicon of glass production, the sex act we now commonly associate with glory holes made its (first historically documented) debut, also in England.

The turn of the 18th century was a particularly rough time for homosexuals (or sodomites, as they had come to be called): A religious revival was rocking Western European society, inspiring new laws to govern sexual practice and deviancy. Incidentally, the increased scrutiny on homosexual and non-normative behavior fostered a lively subculture. It was under this threat of persecution that the term cruising was coined from the dutch word kruisen, meant to describe, according to historian Tim Blanning, the activity of men meeting with other men everywhere from public toilets to the “wooded area near The Hague” to “even the very grounds of the building in which the Court of Holland held its sessions.” Meanwhile, in Westminster, England, journalist Ned Ward reports in 1709 that “there are a particular Gang of sodomitical Wretches in the Town, who call themselves the Mollies, and are so far degenerated from all masculine Deportment, or manly Exercises, that they rather fancy themselves Women.”

As literary historian Rictor Norton points out, it’s in this historical moment that we find the first documentation of a recognizably modern “glory hole,” in a 1707 court case known as the “Tryals of Thomas Vaughn and Thomas Davis.”

In 18th-century London, gay men were regularly arrested in the Lincoln’s Inn bog house, on the east side of New Square, Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The Savoy bog house was used so regularly by gay men that members of the Society for the Reformation of Manners often posted themselves outside and could be sure of making an arrest there. And in the Temple bog house in 1707 a hole had been deliberately cut in the partition wall between two stalls—making it the first recorded glory hole.

To read the actual text of the trial is confusing, but well worth it for anyone interested in the shocking similarities between early modern and contemporary “gay” culture, behavior, and practices. Take one look at the language in the 1707 trial and there’s no mistaking it—we’ve got a glory hole on our hands (emphasis mine):

[H]e having had occasion to go to the Burrough of Southwark, to a Customer of his about some business, in his return took Water, and Landed at the Temple Stairs, but having occasion to untruss a Point, went down to the Temple Bog-House, where he had not been long before a Boy in the adjoyning Vault put his Privy-member through a Hole, which he perceiving was so surprized that he immediately went away; but he was no sooner come out, but the Boy follow’d him, and cry’d out stop him; saying he would have bugger’d him, upon which Vaughan meeting him stopt him, and said unless he would give him an account where he liv’d he would have him secured.

Who knew deviancy was so … traditional? While this is probably not the first time in history someone put his penis through a stall partition, the incident at the Lincoln’s Inn bog house is the first we have on record. It’s hard to tell how widespread the practice was, but as bathrooms (and bathroom stalls) became more common, and homosexuals more persecuted, it’s hard to imagine it not proliferating in kind.

By the time England entered the industrial era, even a whiff of homosexuality could lead to prison or forced labor. In 1885, England passed a law making any homosexual act illegal, with or without a witnessed account. Even overly friendly letters became grounds for prosecution. This gave homosexual men even more reason to hide, lest they ended up like Oscar Wilde. Yet, as homosexuality became riskier in the 19th century, industrialization was packing together massive groups of dirty, hot, sweat-drenched men like never before. And in many of these factories, glory hole was becoming a commonly used industrial term, indicating, in addition to glass furnaces, the “large cavernous openings” of mining and oil drilling and the packed sleeping quarters of nautical vessels.

It’s unclear exactly when some genius queen decided to connect the dots between the various industrial meanings of “glory hole” and apply them to what was going on in the men’s room, but according to The Routledge Dictionary of Modern American Slang, the first time it appears as such in print is in 1949, in the glossary of an anonymously published pamphlet called Swasarnt Nerf’s Gay Girl’s Guide. Finally, we have a recognizable definition: “Glory-Hole: Phallic size hole in partition between toilet booths. Sometimes used also for a mere peep-hole.” Probably no one did more to cement this definition of the glory hole in the cultural lexicon than sociologist Laud Humphreys, who slavishly recorded sexual practices he observed in popular men’s rooms in his ethically questionable 1970 book, Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places, where he defines the glory hole in hilariously clinical terms:

If there is a “glory hole” (a small hole, approximately three inches in diameter, which has been carefully carved, at about average “penis height,” in the partition of the stall), it may be used as a means of signaling from the stall. This has been observed occurring in three manners: by the appearance of an eye on the stool-side of the partition (a very strong indication that the seated man is watching you), by wiggling fingers through the hole, or by the projection of a tongue through the glory hole.

Out of all the places where gay men could hook up, Humphreys argued that the men’s room (or “tearoom”) offered the most advantages to those seeking “homoerotic activity without commitment,” as it was easily identifiable to those looking for action but also private enough to veil activities. Tearooms could “attract a large volume of potential sexual partners, providing an opportunity for rapid actions with a variety of men” and could potentially pop up anywhere, from “department stores, bus stations, libraries, hotels, YMCA’s, or courthouses” to the “restrooms of public parks and beaches” and highway rest stops. Basically, any bathroom, especially if it had glory hole, could be a tearoom (not to say every bathroom should be).

The decriminalization of homosexuality and the onset of the HIV/AIDS crisis sparked the decline of the kinds of tearoom spaces described by Humphreys. By the late 1990s, glory holes were getting harder to come by in the wild, but they became common fixtures in some sexually permissive gay clubs and the backrooms of porn shops. Despite their relative scarcity, a 2001 article in the Journal of Homosexuality found that public glory holes remained popular among many gay men, “simply because they find the places exciting and/or convenient.”

Today, glory holes have mostly been reduced to an artifact of gay history that many look back on nostalgically. In 2018, the Western Australian Museum raised eyebrows by adding a “historic glory hole” to its collection, and some communities have rallied around the cause of glory hole preservation. And even as hookup apps like Scruff and Grindr would seem to render the tearoom unnecessary (and indeed, one sees some users advertising homespun glory holes in their apartments), many men continue to seek out public glory holes for anonymous cruising, with some taking to the internet to share, rate, and describe past and present glory hole and general cruising locations.

The notoriety of the glory hole as a public sex object is not lost on contemporary glass blowers. Despite the glass blowing furnace predating the sex term by at least 100 years, they’ve learned to accept and embrace their professional term’s off-the-clock life. “Glassblowing,” writes artist Karen Sherman, “holds no illusion of role-playing in its language. The jargon is filthy and wonderful and wonderfully homoerotic.” As Sherman notes, the “glory hole” is just one of many potentially suggestive terms among the glass blowing lexicon: “In addition to putting your pipe in the glory hole, you paddle someone’s bottom and you blow them after they jack. One day my instructor said, ‘When you come out of the glory hole you’ll blow, jack, blow, jack.’ I expressed silent gratitude that none of my classmates were named Jack.’”

So ultimately, who owns the term? Sure, the glass blowers may have had glory holes first. But today, a well-crafted vase is hardly the first thing that comes to most people’s mind when they hear the phrase. As is so often the case, it took the gays to engineer the glory hole’s most enduring form and likewise to make it iconic. Fortunately, there’s no need to bicker over possession too much—a glory hole is by nature democratic, open and accommodating to all.