The Raine Island Recovery Project Phase 2 is a collaboration between the Queensland Government and Australian Government and the Wuthathi People and Meriam Nation (Ugar, Mer, Erub) People to re-establish and maintain Raine Island as a viable island. Phase 1 of the Project was a six-year collaboration between BHP, the Queensland Government, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Wuthathi People and Meriam Nation (Ugar, Mer, Erub) People and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

We would like to acknowledge the Wuthathi People from Cape York and the Meriam Nation (Ugar, Mer and Erub) People from the eastern Torres Strait, as the Traditional Owners for Raine Island.

As a sign of respect, Traditional Owner’s language for certain places and animals has been incorporated throughout the image captions on this website.

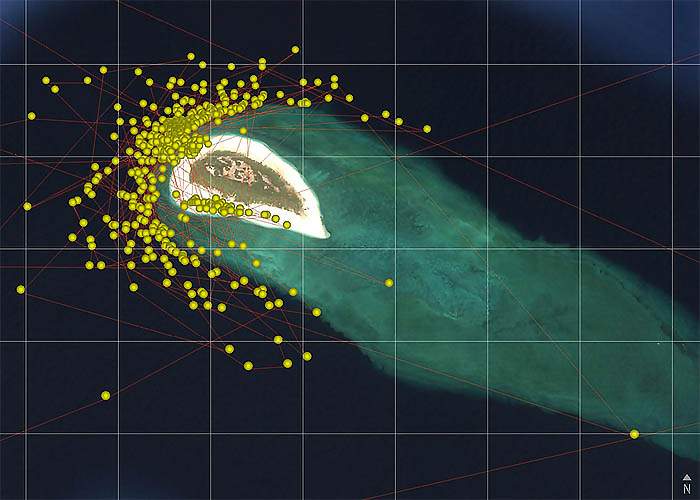

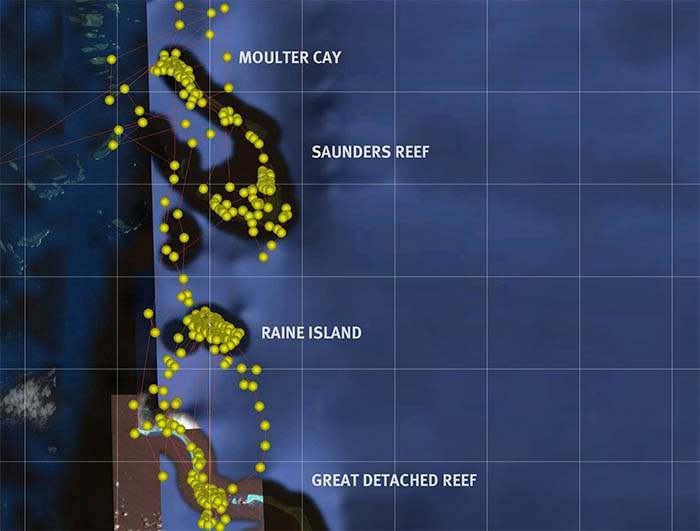

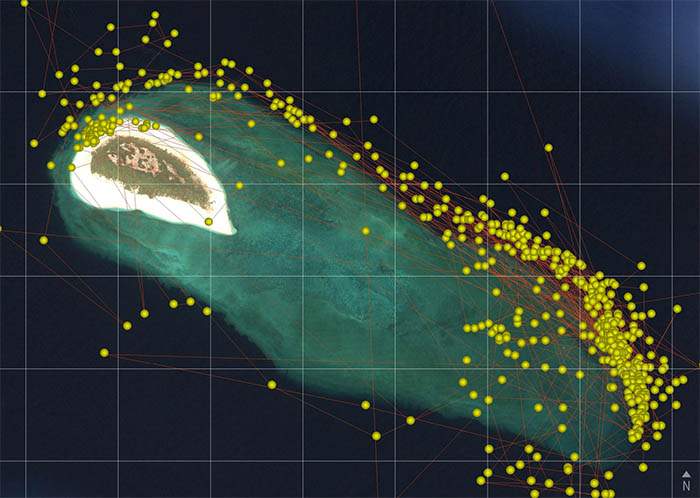

Raine Island is located on the northern tip of the Great Barrier Reef, approximately 620 kilometres north-west of Cairns. The vegetated coral cay is approximately 27 hectares in size, but holds significant environmental and cultural values. The entire island is a protected national park (for scientific purposes) and is not accessible to the public.

Map by Google Earth

Raine Island is:

- supporting the world’s largest remaining green turtle nesting population

- the most important seabird rookery in the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area

- a significant cultural and story place for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- home to a stone beacon, constructed in 1844, which is a landmark of national cultural significance listed on the Queensland Heritage Register

- located in a remote area of the Great Barrier Reef that was the site of numerous shipwrecks, particularly during the 1800s, and even today remains poorly charted.

“A marine paradise that plays host to one of the most spectacular ocean migrations on the planet. This is Raine Island…”

Raine Island with Sir David Attenborough

Ground-breaking intervention works and new research methods are achieving encouraging results.

In September 2014, a 100m x 150m section of the nesting beach was re-profiled by machinery using sand from the island to raise the nesting beach above tidal inundation level.

The first re-profiled area on Raine Island (Bub warwar kaur)

Video of major works to raise beach sand levels

As a result:

- turtles are spreading out when nesting on the re-profiled section of beach, minimising the chance of them digging up already laid clutches of eggs

- there is reduced disturbance from other turtles while laying eggs

- nests are being laid above inundation level at all times

- fewer eggs are dying in the early stages of development.

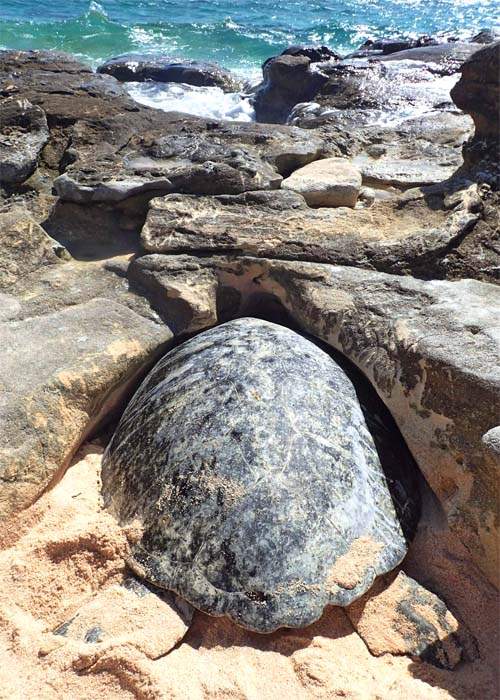

Another key part of the Project is to reduce the number of turtles that die each nesting season from cliff falls, getting trapped in beach rock or exhaustion. The installation of ‘cliff top’ fencing has prevented hundreds of turtles from falling down cliffs on to their backs, and becoming trapped.

Fencing installation to divert turtles (Nam) away from ledges

Trapped turtles (Nam) die at rocky ledges

During every trip to the island, the research crew take a ‘rescue walk’ every morning to flip over any turtles trapped on their backs, remove any that are stuck in beach rocks and carry any exhausted or disorientated turtles back to the water’s edge on the turtle sled or in the power carrier. If these turtles are not rescued, they would overheat and die on the beach.

Power carrier used to transport stranded turtles (Nam) back to water

Sled used for transporting turtles (Nam) back to water

Turtle (Nam) released from sled

1,100m of fencing installed estimated to have prevented 400 turtle (Nam) deaths

Approximately 2,000 turtles (Nam) are tagged each nesting season at Raine Island (Bub warwar kaur)

Five turtles (Nam) have been satellite tagged at Raine Island (Bub warwar kaur) since 2015

Tiger sharks can be found close to the coast, mainly in tropical and subtropical waters, and are known to migrate great distances to Raine Island to feed on green turtles.

Sharks cruise the shallow waters

Recent studies show that tiger sharks are going out of their way to avoid live, healthy turtles, and instead prefer to feed on dead or weakened ones floating in the water around the island.

A tiger shark surfaces

BHP

As a leading global resources company, sustainability is at the heart of BHP’s strategy and is embedded throughout the organisation.

BHP is committed to helping build climate change resilience for the long term to ensure the future of the biodiversity and ecosystems on which our world depends. The company is constantly challenging itself, and its people, to do more to support the environments in which they operate.

Since 2007, BHP and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation have been working together to fund research to protect and restore the Great Barrier Reef—a global company supporting a global treasure.

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service is a part of the Department of Environment, Science and Innovation that is committed to managing Queensland’s parks and forests in a way that sustains natural and cultural values, builds environmental resilience to ensure healthy species and ecosystems and facilitates ecotourism, recreation and heritage experiences.

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority

For 40 years, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority has managed the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park to ensure it is protected for the future. The Authority achieves this by using the best available scientific information and engaging with experts and the community. This includes four Reef Advisory Committees and 12 Local Marine Advisory Committees.

The Traditional Owners

Raine Island is of significance to the Erubam Le, Meriam Le and the Ugaram Le and the Wuthathi People, who are the Traditional Owners of Raine Island. See a map of the Wuthathi Traditional Use Marine Resource Agreement (TUMRA) region (PDF, 9.85MB). Turtles are an important part of Indigenous culture and lifestyle. Traditional Owners want to see Raine Island and turtles that nest there preserved for future generations.

Great Barrier Reef Foundation

The Great Barrier Reef Foundation exists to ensure a Great Barrier Reef for future generations. The Foundation is the Australian charity dedicated exclusively to protecting the Great Barrier Reef through raising funds for solution-driven science. Leading the collaboration of business, science, government and philanthropy, the Foundation funds vital research that goes to the heart of protecting the Reef and building its resilience in the face of major threats.

The Raine Island Recovery Project is also supported by James Cook University, Auckland University, the University of Queensland, the Australian Institute of Marine Science, the Department of the Environment and Energy, the Department of Environment, Science and Innovation, Department of Natural Resources and Mines, Biopixel and We do IT.