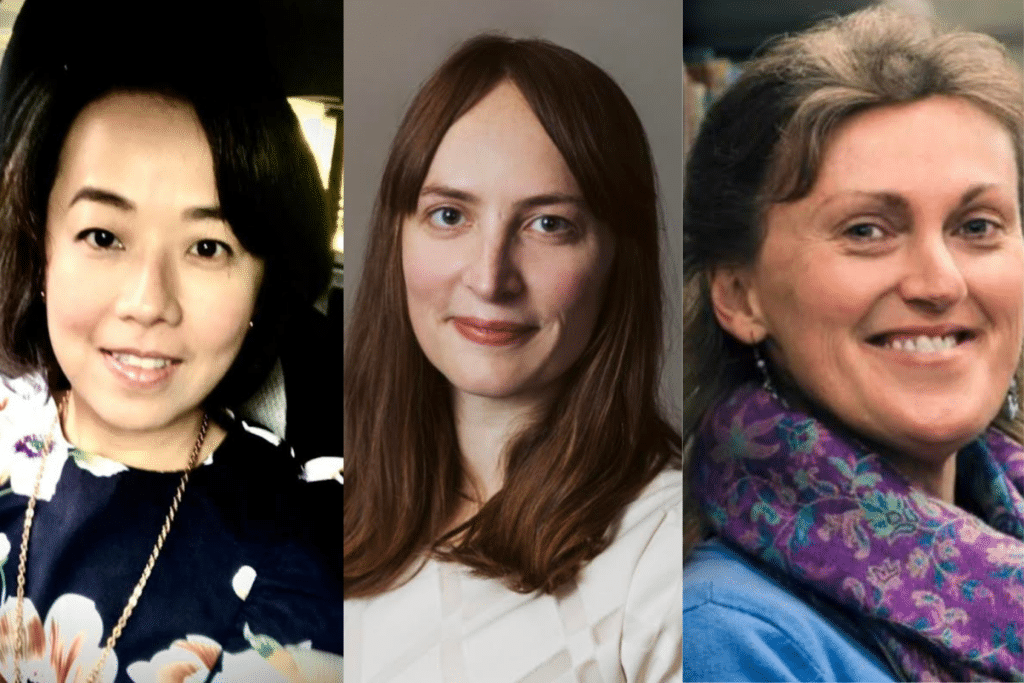

This systematic review into early childhood educator burnout and effective interventions was written by Dr Marg Rogers from the University of New England in NSW, Joanne Ng from the Australian Educator Research Organisation and Dr Courtney McNamara from Newcastle University in the UK.

The alarming number of early childhood educators burning out and leaving the profession affects us all. As a society, it is important that we quickly address the situation, or we will deal with a cascade of negative implications.

Young children are particularly vulnerable. Children are much less likely to bond with educators who are exhausted, on sick leave, or who leave their situations. This impacts the quality of children’s learning, because interactions with known and trusted caregivers are essential for the development of emotional, social, language, cognitive and other skills.

When educators (91% female) leave the sector in areas identified as ‘childcare deserts’, it increases competition for places in these areas where up to three or more families can be applying for one place in an early childhood services. This affects parents, especially women’s ability to access employment and have the financial independence that might assist them to leave unsafe environments and keep their children from harm.

A lack of early learning places also affects businesses and organisations as parents are restricted in the number of days and hours they can work.

It costs the community when we have unwell educators who need extra health and mental health services. Additionally, training new educators to replace those leaving costs us all through taxes.

So we need to understand what burnout is, and what factors affect educator burnout in order to avoid it.

What is burnout?

Burnout is psychological and physical fatigue that is recurring. It can include many symptoms, such as a low sense of personal achievement, emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation (when individuals feel like they are looking at themselves from afar or feel like what is happening is not real).

What factors affect educator burnout?

Our 2023 systematic review examined 39 studies about early childhood educator burnout from 13 countries, including Australia. We found there were both organisational and individual factors that could lead to educator burnout. Unsurprisingly, many of these factors are typical in female-dominated workplaces and in women’s lives in general.

Organisational factors

Poor organisational structure and systems

Educators identified the challenges of working in a sector with high job demands, excessive expectations and a lack of resources to assist them with their work. At the service level, there were problems with mismatched roles and expectations, and a lack of role clarity. Educators also said that working in environments with high turnover affected their work and wellbeing.

They also reported the nature of teaching tasks and parent-oriented tasks were exhausting. Another source of exhaustion was the need to constantly improve quality for accrediting bodies without the structural support needed.

Poor professional relationships

Educators reported an impact on their wellbeing when relationships with directors and colleagues were difficult – a situation common in stressful work environments. Additionally, working with children with challenging behaviours was frequently reported to cause high levels of stress. Some relationships with parents became problematic if the educators felt undermined.

Low professional status, progression and professional development

Educators who felt that society perceived their work as caregivers rather than as educators reported higher levels of burnout. Many also reported their perceptions of low job status got worse during the COVID-19 pandemic, as revealed in international studies. Feelings of low status seemed to increase both for those who had worked longer in the sector, and if they taught younger children.

These two cohorts were also more likely to report a lack of career progression as a source of stress. In general, educators also identified a lack of professional development opportunities as a factor impacting their feelings of burnout.

Lack of wellbeing focus

Services with little focus on educator wellbeing were a factor that increased feelings of burnout. Educators talked about workplaces that didn’t respect work-home boundaries, were not committed to their wellbeing, lacked emotional strategies, or had a stress mindset, but didn’t acknowledge the impact of educators constantly using teacher executive function and didn’t provide recovery experiences.

Some educators also reported the unrecognised exhaustion from surface acting – that is, pretending to feel a certain way to please a child, parent or director.

Individual factors

Demographics

Unsurprisingly, age, gender and family roles impacted educators’ feelings of burnout. Younger, less experienced educators were more likely to report high levels of depersonalisation. Those with other caring responsibilities or who were single due to being widowed, divorced or separated reported higher feelings of burnout. In one study, male educators reported a much higher level of stress and lack of motivation compared to their female colleagues.

Social capital

Educators who reported being well supported had fewer feelings of burnout. Educators mentioned a range of supports, including family, friends and their faith.

Poor health

A crucial factor in educator burnout was poor health. Three studies showed poor mental health was associated with burnout, especially mental distress and depression. Many educators reported poorer mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, as shown in another Australian study.

Low wages

Importantly, low wages played a vital role in educator burnout, with educators seeking work elsewhere if they thought their wages were unacceptable. Additionally, one study linked low wages to absentee issues and poor motivation. The financial stress many educators felt was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, with similar findings in other international studies.

While all these findings sound negative, the good news is that some interventions work well.

What interventions work to counteract burnout?

Two types of interventions were found to be effective:

- professional development that included reflective writing and coaching if there was an opportunity for emotional outlet and opportunities for feedback; and

- psychological interventions with counselling that gave educators the ability to revitalise their motivation, reflect, recover, and better understand their work.

A way forward

To improve the woeful attrition rate of our educators, drastic change is required. This includes the need to:

- recognise our society does not value educators because women provided this service for free in previous times;

- understand the emotional cost of caring and ensure they are not considered both ‘essential’ but at the same time ‘invisible’;

- improve educators’ work and reduce workplace stress by rethinking managerial systems that drive the overwork, fatigue, excessive expectations of the role, and the exhausting pursuit of the government’s notions of quality and data collection to please accrediting bodies;

- pay degree-qualified educators the same as school teachers, and drastically improve the wages of all other educators (who are all either diploma and certificate qualified);

- clarify job descriptions and enforce workloads so educators are not asked to take work home or work unpaid overtime;

- provide more staffing support for children with behavioural challenges;

- provide professional development in areas chosen by educators themselves, including self-care;

- understand and recognise the particular stresses educators faced during the pandemic as essential workers and how that is linked to burnout;

- provide educators with self-care, counselling, coaching/peer mentoring support;

- provide additional support for new educators;

- show gratitude for educator’s work with children and their contribution to the greater community; and

- participate in Teachers’ Day celebrations and educate children to appreciate the work the teachers do.

If we do this, we can have well and happy educators, flourishing children and parents able to work if they want to.

Author Bios

Dr Marg Rogers is a Senior Lecturer in early childhood education in the School of Education, University of New England, NSW, Australia. Her research interests are in families, military families, and educator and children’s wellbeing. Marg is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Manna Institute.

Email: [email protected]

Joanne Ng (corresponding author) works as a Research Project Coordinator at the Australian Education Research Organisation (AERO). Her research interests include educator well-being, leadership, mentoring and multilingualism and multiculturalism.

Email: [email protected]

Dr Courtney McNamara is a Lecturer in Public Health within the Population Health Sciences Institute at Newcastle University, UK. Courtney’s primary research interests reside at the intersection of labour markets, social policy, and health.

Email: [email protected]