Jim Hirschauer was in the market for a Porsche. A rare Porsche. A 469-horsepower electric Porsche.

When he visited his local Austin, Texas, dealership in November 2021 to inquire about one, there were none in stock. But for a test drive, a salesperson wound up borrowing an electric Porsche Taycan he was leasing for his wife. The model wasn’t the exact Taycan—a silent, five-door, all-wheel-drive wagon called the Taycan 4 Cross Turismo, or CT4 for short—that Hirschauer had his heart set on buying. But it proved every bit the seat-pinning, gasp-inducing thrill ride you’d expect of an electric vehicle made by the same nerds who make the 911. After the drive, Hirschauer ordered a Mamba Green CT4 and plunked down a $5,000 deposit. The dealership told him to expect delivery on March 18, 2022.

Now, before you take the 48-year-old marketing exec for a polar bear–saving hero, let’s be clear: Hirschauer wasn’t buying an electric car to reduce his carbon footprint. No, he craved the most visually and mechanically appealing EV he could buy, and the Taycan fit the bill. Even more exciting: This would be his first Porsche. He was buzzing with anticipation.

Via Porsche’s “Track Your Dream” app, Hirschauer followed the car as it was built, then along a 400-mile route from the Porsche factory in Stuttgart to the port city of Emden, Germany. The original plan was for it to board the cargo ship Sonic and then off-load in Houston before completing its final leg to the Austin dealership. But when the truck carrying Hirschauer’s Porsche was delayed near Dusseldorf on the way to port, making it a day late to the Sonic, the Taycan was rebooked on the Felicity Ace.

On February 10, the Ace steamed off from Emden into the North Sea, with Hirschauer’s Taycan aboard. Hirschauer tracked the ship’s progress like a hawk, sharing updates on the Taycan Forum message board with other members who were looking forward to their own deliveries. But then on February 16, Hirschauer read a message board post that made his stomach drop: “Felicity Ace ship on fire in the Atlantic carrying Porsches.” That can’t be good, Hirschauer thought.

According to Portuguese authorities, the Felicity Ace was about 100 miles from the Azores, a constellation of small islands west of the Iberian Peninsula, when the ship made a morning distress call to report a fire in the cargo hold.

By noon the Portuguese Navy patrol ship Setúbal was on scene, flanked by four merchant ships that had come to help and found the Ace spewing great clouds of white smoke across the sea. The crew of a Rotterdam-bound tanker in the rescue armada, the Resilient Warrior, successfully brought all 22 members of the Ace’s crew aboard. After lifting crew members two at a time in a basket from the deck of the Warrior, a Portuguese Navy helicopter flew them to the port of Horta in the Azores. Once the crew was declared unharmed, concern shifted back to the 3,828 cars that were slow-roasting on board, most of them fresh offerings from Volkswagen Auto Group, which owns some of the world’s most well-known and illustrious auto brands—among them Audi, Bentley, Lamborghini, and Porsche.

With little information coming from Porsche, the Taycan Forum became an essential news outlet. Another Taycan Forum member reported that a Porsche they thought was aboard the Ace was actually safe in Emden and coming over on another ship, but Hirschauer wasn’t so lucky—he knew his Porsche was somewhere in the burning ship’s hold.

The Felicity Ace drifted for more than a week before the salvage operation began. The plan was to hook the Ace up to a massive tugboat called Bear and drag it 70 miles southeast of Portugal’s Faial Island, the westernmost point of Europe and the nearest safe place to perform such a tricky operation. (The 650-foot, 60,000-ton cargo ship was too big for any port that far out.) But bad weather and the Ace’s compromised propulsion controls made for a more difficult salvage than workers anticipated.

On March 1, after enduring weeks of rough seas, the Felicity Ace entered into a starboard list and leaned 45 degrees before easing below the surface of the North Atlantic. Its final resting point lay two miles underwater. Somewhere down there is Hirschauer’s Porsche, a trove of unobtainable explanations for the accident, and plentiful targets of scrutiny regarding a shipping industry—and the boats within it—that has been taken for granted.

Our modern consumerist economy thrives on instant gratification. When we want something, we buy it with as little as a click and a credit-card autofill. Sometimes we schlep those new purchases home ourselves. Sometimes they appear on our doorstep within hours of the purchase. Oftentimes these goods are produced a hemisphere away, in places like China—or Germany, in the case of Hirschauer’s doomed Taycan. And yet: Despite the regularity with which we deal with the phrase “shipping and handling,” we usually don’t consider how this process might involve actual ships. As consumer pressure pulls slack out of the supply chain, it increases strain almost everywhere else, especially the shipping industries and accident-prone cargo vessels. It’s fair to wonder: Is any of this sustainable? “The process of preventing these things based on past experience is in a way problematic,” says Kyle McAvoy, a marine safety expert at Robson Forensic, about cargo ship disasters. “It’s always a catch-up game.”

During the pandemic, as cargo ships backlogged outside ports, the phrase “supply chain issues” became occasional shorthand for “lost at sea.” For all of air freight’s efficacy, it costs around five times as much to move a product through the air as it does by sea, according to the logistics firm Freightos. Water remains the chief transport artery for global trade, with around 90 percent of traded goods carried via ship. And all it takes is one clog to trigger a global panic attack.

That much became clear in March 2021, when the 1,300-foot, 200,000-ton container ship Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal, jamming one of the world’s busiest trade routes for six days. The accident, initially blamed on stiff winds, is estimated to have blocked $9.6 billion in trade per day and marooned more than 300 ships outside the Suez’s northern and southern entrances, and those ships carried everything from oil to cattle to cars. While Egyptian crews worked to dislodge the Ever Given, the vessel gained internet infamy as a metaphor for the pandemic age.

You’d think that a ship the size of the Empire State Building would be able to withstand the stresses of a gusty day. But in the shipping business, margins matter. For decades, cargo ships have been steadily growing in size in order to carry more freight on each voyage. The German insurance company Allianz estimates that capacity for 20-foot shipping containers alone has spiked by 1,500 percent over the past 50 years. In 1990, the largest ships could hold 5,000 containers. The Ever Given carries four times that.

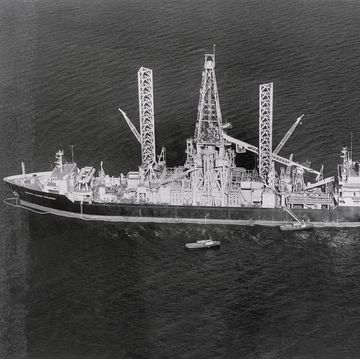

The Felicity Ace, while nearly as large as that ship, is built differently: It falls into a category of freighters called car carriers. In the mid-sixties, the average carrier might have accommodated a thousand cars. The Felicity Ace could hold about 4,000. That growth isn’t just the consequence of a more interconnected automotive industry. It’s been turbocharged by the expansion of the Panama Canal. Car carriers are built to be as big as the largest size allowable through the canal’s locks and bridgeways. They carry heavy vehicles such as cranes and earth movers below deck as a weather safeguard, and unlike containers, which have to be lifted off of ships, carriers allow for cargo to be rolled on and off. Hence their nickname—RoRo ships.

If the Ever Given is a skyscraper, the Felicity Ace was a floating parking garage, with the ability to configure its decks based on the size of the cargo, the balance requirements of the ship, and the shipping route. Stevedores—the dockworkers who load and offload shipping goods and arrange cargo based on which cars and trucks need to roll off first—take great care in tying the vehicles down so they don’t shift in transit. To make the most of the space, they pack the vehicles a foot apart from bumper to bumper, and about six inches from side to side, folding their mirrors in when possible. At port and in transit, they inspect the tie-down lines regularly. A breakaway car could result in millions of dollars in damage to other vehicles and wildly throw off the balance of the carrier itself.

For as critical as these massive cargo ships are to our global economy, they’re not especially maneuverable. The Queen Mary 2, the largest passenger ship at the time it was built, is downright balletic compared to the Felicity Ace, which is about half the size; the cruise ship has to be more agile to ensure that passengers don’t get tossed around. But since cars don’t get seasick, RoRos aren’t designed to be super stable—that would be expensive, which would drive up the cost of shipping and eat into those all-important margins. So carriers are built with just enough capability for the job. That can make them prone to accidents.

It doesn’t take much to bring down a RoRo. In 2002, a Norwegian RoRo called the Tricolor collided with a container ship 20 miles off the northern coast of France. While the other ship sailed on, the Tricolor sank and took about 3,000 BMWs, Volvos, and Saabs down with it—a $50 million load. After a cargo ship and an oil tanker crashed into the wreck in the English Channel, the Tricolor and its contents were cut into nine 3,000-ton sections and steamed off to Belgium for disposal. That salvage cost another $40 million.

The Bay of Biscay, along the coast of France and Spain, hosted two RoRo accidents in three years. In 2016 the Modern Express developed a 40-degree list under heavy winds before the company that operated it deemed it beyond repair; it was carrying 3,600 tons of earth-moving equipment and logs. In 2019 the Grande America caught fire while transiting the Bay of Biscay en route to Casablanca, and sank. It’s still sitting there, leaking oil from its tanks and entombing some 2,100 vehicles.

On the U.S. side of the Atlantic, the Golden Ray capsized in St. Simons Sound on its way out of Brunswick, Georgia, in 2019, trashing about 4,200 cars—most of them factory-fresh Hyundais and Kias. A 2021 NTSB report attributed the cause of the accident to a miscalculation of the ship’s balance. In the end, the Golden Ray was cut into eight sections and hauled off to Louisiana for scrap. That salvage operation—delayed by the pandemic and three hurricane seasons—took over two years and cost nearly a billion dollars. That doesn’t include the cost of the ship ($62.5 million) or the cars ($142 million).

Insurers put the value of the Felicity Ace’s cargo at around $400 million. Among the writeoffs were a handful of standout, single-owner cars (a nineties-era Honda Prelude SiR, a 1977 Land Rover Santana, a 2019 Mini Countryman packaged in a wooden crate) and 12 Fendt tractors. The Volkswagen Group cars on board included 190 Bentleys, 85 Lamborghinis, 580 Porsches, and 846 Audis. A significant chunk of the losses were EVs like the VW ID.4, the Audi e-tron, and Hirschauer’s Taycan.

Experts have speculated a battery fire might have brought the Ace down. Overwhelmingly, modern EVs draw power from lithium-ion batteries—a fuel source that yields longer vehicle range at the risk of notorious chemical fragility. Several EV makers have had to recall cars amid reports of vehicles spontaneously combusting. Two years ago a Taycan combusted while parked in a Florida garage, damaging the building’s structure and exposing parts of the vehicle’s frame. In the bowels of a car carrier, a chain reaction from such a fire could be devastating.

For years, insurers have been sounding the alarm on the risk of massive ship fires, which, along with explosions, account for a quarter of the maritime casualties for “total loss.” They say firefighting capabilities have not kept pace with the rate of freighter supersizing. Even with regular drills and certification, ship crews still risk being overwhelmed in a massive blaze—especially if one were to flare up beyond the engine room, where crews can at least count on some backup from a C02 system or another passive suppressant. But if an EV tied down in the hold were to catch fire, crews would have to flood the fire to ensure it was extinguished; a lithium-ion battery will reignite otherwise. That would potentially ruin other cars on board and upset the ship’s carefully calculated balance.

While McAvoy, the marine safety expert, acknowledges that shipping safety still has room for improvement, experts have also taken valuable lessons from past calamities at sea. McAvoy credits the introduction of thermal detection, fire-retardant shipbuilding materials, and closed-circuit video cameras for safeguarding not only the cargo but also crew members, who were much less likely to be rescued before ships adopted GPS systems in the nineties. “I like to look at how far things have come,” says McAvoy, who investigated maritime casualties as an officer in the Coast Guard. “In the old days, ships would be lost and no one even knew about it. And a lot of lives would be lost. Things have evolved in the world of shipping safety.”

If any stevedores or merchant marines have trepidations about handling electric vehicles, they aren’t saying so publicly. These shipments keep the lights on at ports and workers employed the world over. A negative word could be as upsetting as a ship stuck in a canal.

It’s likely we’ll never know what actually brought down the Felicity Ace. Not only is the ship 9,100 feet under the sea, but so is its voyage data recorder—the maritime equivalent of an airliner’s black box. What’s more, the waters around the Ace are visibly—and legally—murky. That specific area of the Atlantic, on the Extended Continental Shelf, lies just beyond Portuguese sovereignty. Portugal could let the ship lie—even if that has devastating effects on the ecology of the Azores, which are a magnet for whales, dolphins, and other sea mammals. According to Ana Colaço, a marine researcher at the University of the Azores, the ocean floor where the Ace landed could be teeming with sea creatures lower down the food chain—like sponges and coral, pillars in marine life vitality.

Besides the toxic materials in the vehicles, the ship itself carried 4,400 tons of fuel and oil. The Portuguese Navy has been breaking up the viscous slicks around the shipwreck and remains bearish about the possibility of a widespread spill. If the Golden Ray accident is a guide, any effort to salvage the Felicity Ace could be even more cost-prohibitive than letting it stay at the bottom. The Ray, at least, wound up only half underwater after capsizing.

The Felicity Ace, meanwhile, is stuck in a nautical no man’s land—beyond salvage, according to the VW Group. And because there were no casualties from the accident, there’s no urgency to perform an autopsy on the wreck.

In the absence of clear maritime jurisdiction, there’s been a rush by rubberneckers to apply playground decree—finders keepers—on the sunken cargo. But those rules only apply on land. Legally, just because the crew abandoned ship to save themselves doesn’t mean the ship’s owner abandoned its claim to the vessel and the cars therein. Yes, the cars might be worthless. But ultimately that’s for the Ace’s wards to decide. And any adventurer who goes out looking for treasure on the ship risks real prosecution.

As for the customers banking on that haul of vehicles, they’ve had to start over. VW said it planned to work out “individual solutions” with customers. Lamborghini, which lost 15 specimens of the Aventador Ultimae—a supercar in the midst of a 350-unit swan-song production run—pledged to rebuild them.

And even though Porsche effectively made the same promise to its customers, Jim Hirschauer wasn’t thrilled about being sent back to the end of the Taycan queue. His new wait time for a car is five to six months, and that’s on top of the time he already lost with the Ace going down. Worried that global events—primarily the war in Ukraine (a major automotive parts supplier) and the ongoing chip-supply shortage—might delay his dream car even further, Hirschauer found another CT4 in Louisville, Kentucky. But it doesn’t have the same leather seats, or the door cards that match the chalk exterior color. He’s still waiting for his one true Mamba Green Cross Turismo that Porsche is rebuilding for him in Germany. And when it finally whirs onto another RoRo, he won’t be the only one waiting to exhale until his ship comes in.