Honey Meconi—a professor of music and chair of the department in School of Arts & Sciences, and professor of musicology at the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester—explores the life and work of the Benedictine nun, healer, and composer in a recent book, Hildegard of Bingen, published by the University of Illinois Press in its Women Composers series. It’s the first book in English about Hildegard as a composer.

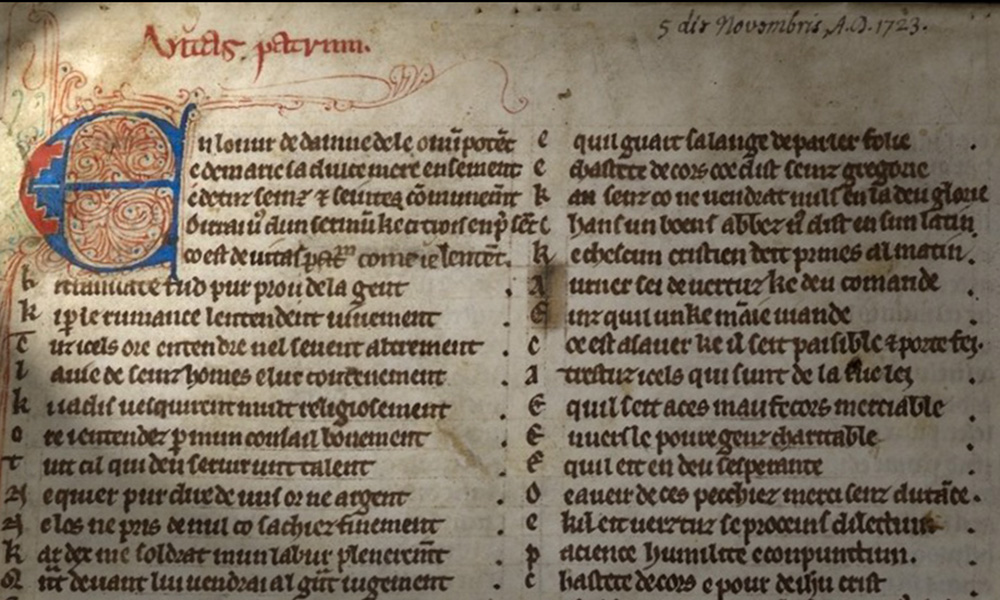

A performer as well as a scholar, Meconi began directing early music groups as a student at Indiana University. She founded and directed ensembles at multiple universities, including Harvard University, where she received her PhD. She is an expert in European music before 1600 and is director of the Hildegard Project, a long-term project to perform all of composer’s music at various venues. In addition to Hildegard, Meconi’s interests include Franco-Flemish composer Pierre de la Rue, and medieval music manuscripts known as chansonniers. She is also a champion of women and music projects, and is the former director of the University’s Susan B. Anthony Institute for Gender and Women’s Studies.

Q&A with Honey Meconi

Who was Hildegard of Bingen?

Rochester research in The New Yorker

In a January 2023 issue of The New Yorker, music critic Alex Ross examines how Hildegard of Bingen became a towering figure in early music history. As part of his analysis, Ross references music professor Honey Meconi’s book Hildegard of Bingen (University of Illinois Press, 2018) and English professor Sarah Higley’s monograph Hildegard of Bingen’s Unknown Language: An Edition, Translation, and Discussion (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Meconi: A 12th-century Benedictine nun who had extraordinary visions. She wrote about these visions in theological books, and she used them as inspiration for compositions. She founded her own abbey, created her own language, and wrote one of the first musical plays. She was a wonderful composer who set her own lushly poetic texts.

What inspired you to write about her?

Meconi: When I was a graduate student, I was asked to be musical director of a performance of her play—she wrote a whole musical play, the equivalent of an opera. I had never heard of her before that, and this is what brought her to my attention.

When I started teaching in 1987, I wanted to include women composers in my classes. When I was a student, we never studied any music by women—it was simply not part of any curriculum. I now teach early music, music before 1600, and Hildegard is the best-known example of a female composer during that period. I began teaching her, and since I was directing an early music ensemble, it was the perfect opportunity to perform more of her music. That’s how it all got started. It’s fantastic music, and people really enjoy learning about her. How could I not want to write about her?

What fascinates you about her music?

Meconi: What’s interesting is what we create with her compositions, which in her time were used in church, as part of a religious service. Today some people still use her music in church services, but most often it appears in concert performances. And because it’s just a single line of music—it’s plainchant—people then use that as a jumping off point to do all sorts of different things. For example, sometimes performers improvise instrumental accompaniments—by a harp, for instance—or maybe they’ll add drones. That’s when some of the musicians hold a single note, and then Hildegard’s melody unfolds above that.

So when you hear her music on YouTube or on a CD, it’s probably not what it sounded like during Hildegard’s time. I like to use the term tabula rasa, blank slate, for her music. People then hang their own musical ideas on this blank slate. I gave a lecture once where I played 14 different recordings of Hildegard, and the audience assumed they were all separate pieces. But they were really the same composition, in wildly different performances. That’s how freely modern musicians approach these works.

What’s inspiring about her life story?

Meconi: One the things I love about her is that she was 42 before she started writing anything down. In a sense, I think of her as the patron saint of “late bloomers.” Interestingly enough, that slow start is typical of many women who are initially not confident in their abilities. It’s only as they get older and gain more confidence that they start really making a mark in the world.

Hildegard was also someone who didn’t accept her place in the world. She wrote her books, and created a new language, and, in a male-dominated church, she went on preaching tours at a time when women were not supposed to preach, especially in public. She refused to behave in a certain way. She wrote at a time when, if the church authorities had not thought she was divinely inspired, she could easily have been put to death as a heretic.

What did she contribute to healing and medicine—as medicine was understood in her time?

Meconi: She wrote two books that are connected with healing. Physica was about how items in the physical world (plants, gemstones, fish, etc.) could be used in healing. Causes and Cures goes into personal health more directly, such as the importance of following a different diet in the winter than in the summer. During the Middle Ages, monasteries had their own infirmaries and were places that people might go to if they were ill. So it’s natural for Hildegard to have known about healing. Also, as a Benedictine nun, she advocated and practiced moderation and balance—two things we recognize today as being important for well-being. She’s really one of the first people to write in such detail about healing and health, and she’s almost certainly the first nun to do so.

Hildegard seems to be enjoying a moment in the sun these days. The character “Hild” shows up as a revered saint on the BBC series The Last Kingdom, and Hildegard is also mentioned in Netflix’s Chilling Adventures of Sabrina. What do you think of the popular appropriation of Hildegard?

Meconi: It’s great! I think that we live in a world that tends not to pay any attention to historical figures or history. I’m delighted when historical figures become part of popular culture. I don’t agree with all the things Hildegard said or wrote, but I think there are many ways in which she’s a good role model. She went out and created the things she believed in. She didn’t let restrictions that other people placed on her stop her. And if these television shows look to her as a popular inspiration, that’s terrific!