Traditional owners from western Arnhem Land say they are the “original archaeologists” of their country, and now they are taking action to preserve their priceless history on their own terms.

“Many of the stories are still hidden away from non-Indigenous people who have learned very little about them,” Bininj traditional owner Conrad Maralngurra says.

“They need to live with us for 10 or 20 years to get the whole meaning of cultural integrity.”

This week, a group of Bininj traditional owners from the breathtaking stone country of western Arnhem Land travelled to Darwin to present a digital portrait of their country and culture focused around rock art to the annual conference of the Australian Archeological Association.

Berribob Watson, of Manmoyi, and Maralngurra, of Mamadawerre, two small outstations on the Arnhem Land plateau about 300km east of Darwin, detailed the work of nearly 200 Bininj Aboriginal people and addressed the conference in English and Bininj Kunwok (dialects of western Arnhem Land).

“We spoke to them as the original archeologists of our country,” Maralngurra says.

“We have been writing it [history] down from the start, on the rock. Stories on that rock is the law, our heritage and gives people their rights.”

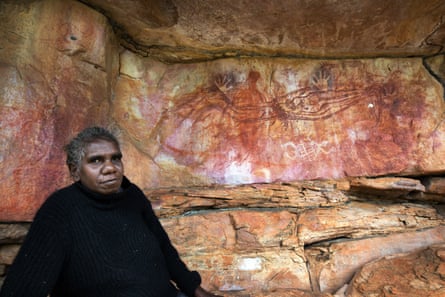

Bininj are traditional occupants of western Arnhem Land, which borders Kakadu and Nitmiluk national parks in the west and south-west. The region’s Kombolgie sandstone has been carved by a cycle of wet and dry seasons over millennia and is one of the world’s most remote and inaccessible regions. Indigenous occupation goes back to the last ice age. Rich rock art is liberally scattered on the walls and ceilings of sandstone shelters.

It is estimated there are three or four art sites for every 10 sq km of rocky terrain, potentially more than 40,000 sites. Most art is in or near areas where Bininj lived for thousands of years. While some sites are specific to men or women, most are communal.

In the recent past, rock art research has been the domain of non-Indigenous anthropologists and archaeologists employed by tertiary institutions with government funding. Their findings, including interviews with traditional owners, photographs and artefacts taken from sites, often remained with institutions where they were archived. Rarely did the data come back to a community in any form other than a research paper or government document.

However, Bininj have turned that model on its head.

In 2010, Aboriginal elders from the Warddeken and Djelke IPAs established the Karrkad-Kandji Trust to seek alternative sources of funding for land management and cultural projects. The trust approaches Australian and international philanthropic organisations and individuals.

The KKT established a $5m rock art project in Arnhem Land, the main contributor being the Ian Potter Foundation. Bininj hired their own support staff – Claudia Cialone and Chester Clarke – to live in their communities and coordinate a program to help Bininj locate, record, preserve and maintain sites and artwork.

“We employed these people because we want them to help us preserve the stories through Balanda [European] ways. We also want to share the stories but we want to take control and have legal ownership of the knowledge. We want to maintain, preserve and protect it for the benefit of our own country and people,” Maralngurra says.

The rock art program has an annual budget of $800,000 and employs more than 50 traditional owners and 100 Indigenous rangers, who spend much of their time travelling through remote areas to locate sites. Art is recorded by camera and video, and appropriate landholders are interviewed. The information is stored digitally for future generations.

According to Claudia Cialone, Warddeken land management has built a unique rock art conservation team.

“An academic paper is not enough to express Bininj passion and interest in rock art, so they decided to create their own narrative and take that to the world,” Cialone says.

Maralngurra said the program is sparking interest all across western Arnhem Land and people in larger settlements, who have not been back to their traditional country, are clamouring to return.

“Rock art is at the root of our society,” he said. “It is where we get the stories from. There is a lot of enthusiasm for people to go back and see where their story was established.”

There are more than 125,000 known rock art sites in Australia, from the Torres Strait to Tasmania.

Some contain grand, elevated galleries while others may hold a single, faded image on an out-of-the-way rock face or cave wall. Artistic styles include paintings, rock engravings (petroglyphs) and beeswax motifs and designs. Scientists believe some examples to be 30,000 years old.

Rock art hotspots include Arnhem Land, the Kimberley and the Pilbara.