I roll my pants up over my knees and sink into the soggy ground, squinting at the tall grass in front of me. I ask Mike, my guide, for direction.

“Look at the bottom of the blades,” he tells me. “If it’s purple, it’s wi-kwah-skwah and you can pull it up by the root.”

How to say "sweetgrass" in Cree

Down to the mud I go, leaning on my hands and pushing muck aside to peer at the bases of the grass blades. Triumphantly, I find a purple one and pull it up.

Mike then instructs me to place tobacco on the ground as an offering. I pinch dry shredded tobacco from a pouch in my pocket and place it on the spot I had cleared. I continue on, harvesting more blades. Combined with my partners’ hauls, we eventually collect enough to make a braid.

How did I, a white woman and former high school teacher living in Missoula, Montana, find myself in a sweetgrass enclosure on the Rocky Boy’s reservation, high in the Bears Paw mountains just 60 miles south of Canada, pulling up plants and putting down tobacco?

It’s a story that started eight months ago, but in truth much longer: over a century, or perhaps 500 years. This experience is part of an Indigenous language revitalization effort which is critical to the very survival of Indigenous cultures and to which non-Natives can contribute – but carefully.

According to the United Nations, an Indigenous language is lost every two weeks. Unesco has designated this the decade of Indigenous languages. Successful revitalization efforts are crucial because language is the underpinning of culture. Without language, there are no ceremonies. Entire cultures vanish if the people within them can no longer express their identity in the same ways they have done for millennia.

This most devastating loss is a direct result of colonization, primarily by European settlers over the last few centuries. With every required English class, every tax code, every Eurocentric approach to our society, from education to governance, colonization is perpetuated. And languages continue to disappear.

Michelle Mitchell (Salish), the director of Tribal Education for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, and I talked about this. She said language is crucial because it sustains stories. “Stories tell us who we are. It tells us our place in the world … It tells us everything that’s important as Salish, Pend d’Oreille and Kootenai people. What if the one person who knows about a certain tradition passes away? We lose that knowledge, that gift, and that practice of who we are,” she says. “We have to hang on to the things that we have … to show our children how to heal, to be resilient, how to recognize the strength and the beauty of who we are as people. We have to do whatever we can to preserve it.”

Those stories require facility with heritage language – both understanding it and speaking it.

A tiny part of the effort to preserve Indigenous languages falls under the purview of online education. I spent over two decades teaching high school and living on the Flathead reservation in western Montana and transitioned to a new position at the Montana Digital Academy, our state’s virtual school. In this role, I develop online courses for high school students in the Indigenous languages of Montana.

It is appropriate to ask: why hire a white person to do this work? I am certainly not qualified in terms of my language or cultural knowledge. Yet my longtime close connection with tribal people from years of working and living on the reservation allowed me to reach out to them for guidance and support in ways others in my office could not. I also possess teaching expertise and skill in developing online classes. For me, this has been a way to maintain some of the bonds I built on the reservation while forging new ones through these language preservation efforts.

The job is not easy. Depending on how you count, there are about a dozen Indigenous languages in our state, and every one of them has its own set of protocols about who can provide materials, and which parts of the languages and culture can be shared. I cannot do my job without the assistance of tribal language experts like Mike Geboe (Chippewa Cree/Northern Arapaho), the data analyst for the Chippewa Cree tribe’s department of Indian education at Rocky Boy.

Sometimes I’d text Mike with a list of things and ask: “Can you record these for me?” A few minutes later, I’d have a text back with English and Cree recordings of the words, like sun:

How to say "sun" in Cree

and respect:

How to say "respect" in Cree

Early on in my interactions with Mike, I was told I needed to demonstrate respectful intentions toward the work. “How do I do that?” I asked over the phone. I felt like I had good intentions, but Mike had been hinting for weeks, I thought, about a gift protocol involving tobacco. I didn’t know what that meant.

Finally, probably realizing I was never going to take his cues, he adopted a direct approach. He told me: “You need to give tobacco to the people who are going to help you build these language classes,” meaning the folks in his department. I said I could do that and asked for his mailing address. He said, “It’s better if you bring it in person.”

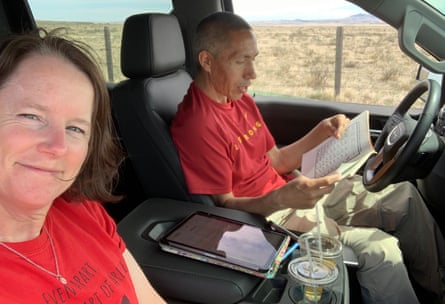

A few moments of silence passed as I realized I’d have to drive 500 plus miles, or a nine-hour round trip, over the mountains and onto the plains, north toward Canada.

The next week found me behind the wheel, tobacco packets in hand.

After my visit, I started to think about all the other ways I hadn’t understood what I needed to do.

I know that educating me is not the responsibility of Indigenous people, and that I owed Mike a debt of gratitude for his extra efforts. But what else didn’t I know? And do non-Natives even have a place in this language revitalization movement? I wondered.

When I asked Michelle about this, she said allies remain important. “We are always going to need advocates supporting our efforts to heal ourselves and our communities, whenever there’s opportunities. We need to make sure that our voices are at every table. For example, if there’s a meeting going on, and we’re talking about tribal people but there’s no tribal people in the conversation, that’s a problem. A non-Indian ally can voice that need.” Specific to the language efforts, she added that “the work is ours to do, but everyone needs support and partners”.

Anishinaabe writer Chris La Tray (Little Shell tribe of Chippewa Indians) also told me that non-Natives have a role to play. “We are all relatives. We are all in this together, and we must work together if we are going to preserve anything at all. Languages, the world, everything.”

However, allies have to know how to act. I asked Michelle what suggestions she has for them. She emphasized that non-Natives can’t be telling tribes: “This is what you need to do.” Instead, they must recognize that each tribe is a sovereign nation and “what worked for one tribe is not going to work for all tribes. You have to figure out what does work and if you get a no, you humbly accept your no and move on.”

In so many ways, white people require education in order to be effective allies. The gift in advance, for example, is something my white, western culture is generally ignorant of. I’ve been the recipient of these gifts as well, and did not understand at the time what they meant: that demonstrating those respectful intentions up front, rather than thanking for a past effort, is a key cultural feature of many tribal communities.

Non-Natives also often need to learn different outreach approaches. For example, many of us use impersonal email technology to communicate with strangers, and in tribal communities this may be insufficient. Face-to-face relationships are crucial.

When I chatted with Michelle about this, she explained: “You can’t expect anything from anyone unless you have that relationship first. You can’t expect a response from a cold call. Even if it’s help you’re offering.” Meeting with tribal people means helping elders, pouring coffee, asking about their children, all prior to any kind of conversation about the meeting’s purpose – if you even get to that.

I recently visited some language and culture experts at Little Big Horn College on the Crow reservation and spent the better part of an hour chatting about beadwork, Crow history and the Star Wars Lego builds on the host’s conference table. At the very end, we discussed a kind of plan about how to progress toward a working relationship with tribal language experts whose experience could inform the class I was building – “email me later” – and that was the visit.

Being absolutely still and quiet, often for long stretches, while elders or other tribal members speak, is an unfamiliar communication style in much of American mainstream society. Non-Natives want to chime in with our thoughts and experiences, say “uh-huh” or at the very least, nod … but often, these noises and motions are considered interruptions. I recall a time when an Indigenous guest speaker was sharing knowledge at the school where I taught. A white teacher began to add an uninvited rejoinder and elicited a loud “Excuse me, I’m still talking” from the speaker. I have witnessed this many times, and it has happened to me.

Finally, non-Natives have to learn to step aside. I wanted to know Michelle’s observations about this. She told me, “I have seen non-Natives that have been working alongside us for a length of time, make the mistake of thinking that because they’ve done that, they can speak for us. I don’t think any people, ever, want that for themselves. We all have our own voices and our own stories to tell. People need to recognize too, that no matter how long someone works alongside of us, they can never be us. It doesn’t matter how well-intentioned you are, you can never have our perspective. Just because we welcome you in, doesn’t make it yours.”

Following the initial visit to Rocky Boy, I had very positive interactions with those helping me to build the Cree class. Later, I’d send the crew there a short video showing them what I’d made for students to engage with – a drag-and-drop feature, for example, or flashcards with photo and audio attached – and they’d tell me to change a detail here and there, or say it looked good to them.

All through the early spring and summer, I drove back again and again. I learned about plants, landmarks and the cultural importance of everything we saw and talked about. It all went into the class I was developing, and into my own mind and heart. I try to build relationships to create accurate learning experiences that are culturally aligned with each sovereign tribe’s wishes. And while assisting in this work, I am learning too: the languages of unique cultures and customs.